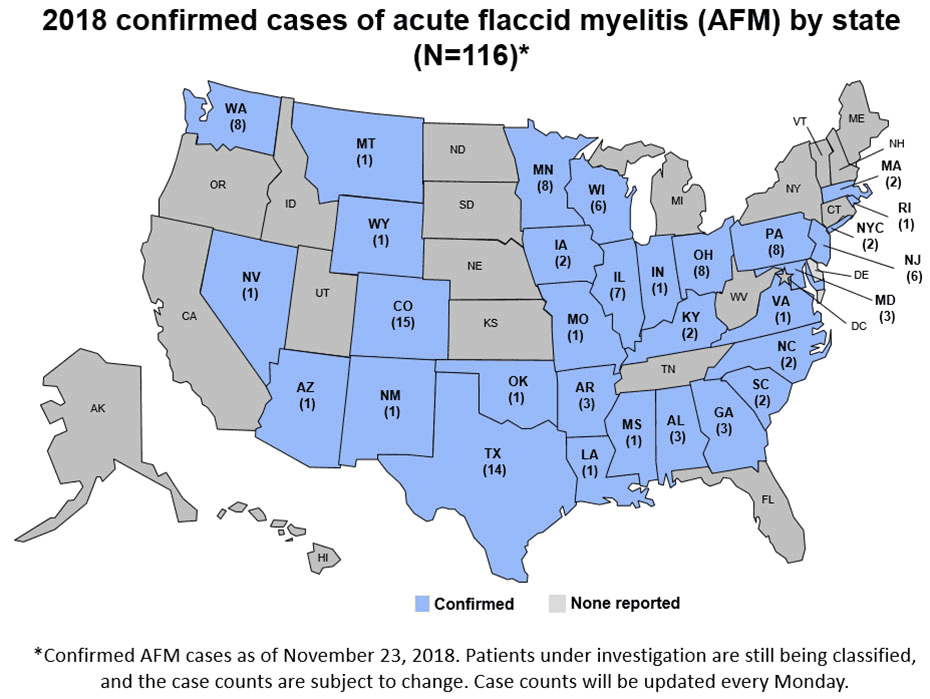

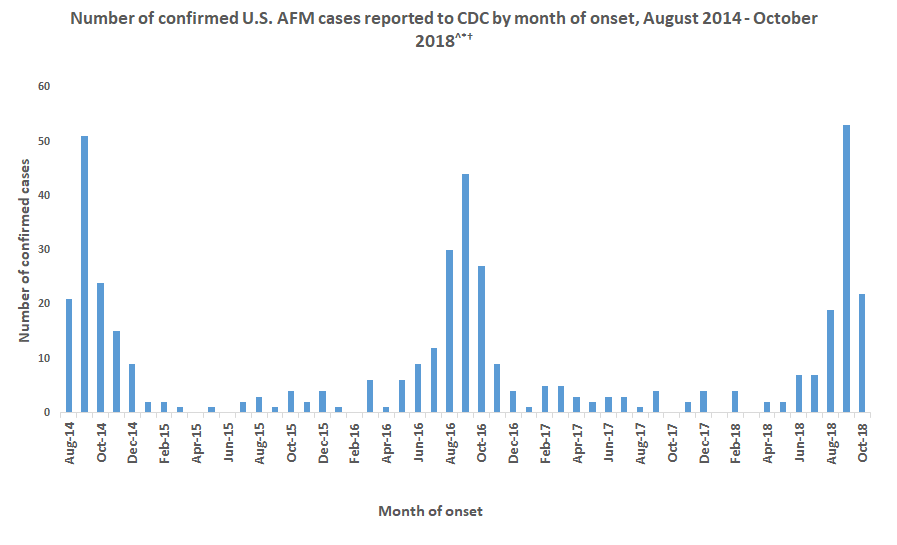

Acute Flaccid Myelitis (AFM), associated with enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) infection, has become an epidemic. Until the summer of 2014 few cases of EV-D68 infections were diagnosed. Subsequently biennial outbreaks have occurred in 2016 and 2018; during which the number of confirmed cases of EV-D68 associated AFM has increased. At least 650 children in the United States have suffered some level of paralysis from AFM, often resulting in long-term physical deficits. Yet, many children and adults are infected with EV-D68 without developing AFM.

Many aspects of EV-D68 biology within the pediatric population remain unexplored including pressing questions about virion antigenicity, mechanisms of virus neutralization and durability of immunity. It is therefore imperative to define the composition of the humoral immune response elicited during EV-D68 infection.

Other enteroviruses, collectively called non-polio enteroviruses (NPEVs) are ubiquitous human pathogens. More than 110 NPEVs have been identified including echoviruses, Coxsackieviruses A and B (CAV and CVB), and EVs A and D (EV-A and EV-D). Infection with these small single-stranded (+) RNA viruses, particularly in children under the age of 6 years, can cause a broad-spectrum of serious illnesses including a polio-like childhood paralysis known as acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), neonatal sepsis, aseptic meningitis, myocarditis, hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD), respiratory illness, and encephalitis.

The prevalence of NPEV-associated pathologies, such as neonatal sepsis, may be as high as 7 in 1000 live births. The Centers for Disease Control estimates that there are 10-15 million cases of HFMD annually. The NPEVs also include human rhinoviruses (HRVs), of which more than 160 genotypes have been identified. Development of severe respiratory complications, including pneumonia and bronchiolitis, especially in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis and asthma, are associated with infection by both HRV and EV-D68. Biennial case surges led the NIH to declare AFM a global epidemic in 2019. These data illustrate the clinical importance of NPEVs and attest to their socioeconomic impact. It is therefore imperative to gain a better understanding of NPEV biology and the associated diseases.

To understand immunity against virus infection, an appreciation of the interactions between the virus particle and the antibody are a first step. How infections occur and lead to severe disease, and the role of systemic immunity must also be acknowledged. Unlike many other viral infections, resolution of NPEV infection by the host is thought to be highly dependent upon the humoral rather than the cellular immune response. Patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia or common variable immunodeficiency are more susceptible to infection with EVs, including HRVs, and echoviruses. Furthermore, many immune deficient patients infected with echoviruses, particularly echovirus 11, develop severe disease including enteroviral associated meningoencephalitis. Moreover, an adult who was treated previously with monoclonal antibody therapy targeting the B-cell receptor CD20 developed meningoencephalitis and AFM after infection with EV-A71. These observations suggest that the presence of a protective systemic antibody response is critical for resolving infection. NPEVs enter the host via multiple routes including the respiratory and alimentary tracts, and the primary site of infection is thought to be within cells of the epithelial lining of the gut and respiratory tracts. The development of severe disease is linked to sites of secondary infection within the body such as the central nervous system and the heart. With the exception of poliovirus, we do not know how diverse NPEVs disseminate to secondary sites of infection. How antibodies and antiviral T cells may interrupt this process has also been understudied.

Our laboratory is currently engaged in research to understand immune responses to NPEVs and their role in modulating disease outcomes.

After its global emergence in 2014, subsequent outbreaks of enterovirus D68 occurred in 2016 and 2018. The expected outbreak of 2020 never materialized, likely due to masking and physical distancing put in place for the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. As these measures are relaxed in multiple countries, increased in cases of respiratory virus infection have been observed, including enterovirus D68 in Europe.

After its global emergence in 2014, subsequent outbreaks of enterovirus D68 occurred in 2016 and 2018. The expected outbreak of 2020 never materialized, likely due to masking and physical distancing put in place for the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. As these measures are relaxed in multiple countries, increased in cases of respiratory virus infection have been observed, including enterovirus D68 in Europe.

CDC has established an AFM task force to encourage collaborations between CDC and the scientific community so that we can better understand the cause of AFM, how to prevent it, and how to treat it. More information on the task force can be found

CDC has established an AFM task force to encourage collaborations between CDC and the scientific community so that we can better understand the cause of AFM, how to prevent it, and how to treat it. More information on the task force can be found